I vividly remember these ‘mathematics learning aids for students’ at primary school. This would have been at the very start of the 70s when Cuisenaire rods were at the height of their popularity.

Until quite recently I’d assumed they were called ‘quizinaire’ having never seen the word written down and only rarely spoken. They were always simply ‘the coloured rods’ which lived in the bright red plastic drawers at the front of the classroom.

The ten rods measured 1cm to 10cm with each increment represented by a different colour:

White 1cm

Red 2 cm

Light green 3cm

Pink 4cm

Yellow 5cm

Dark green 6cm

Black 7cm

Brown 8cm

Blue 9cm

Orange 10cm

The rods were the invention of Belgian primary school teacher Georges Cuisenaire in the early 50s. Cuisenaire found that pupils who had difficulty with maths taught by traditional methods learned quickly when they manipulated the rods. Child centred learning emphasised learning by play and Cuisenaire rods were a central part of the new ethos.

Magpie maths

In truth, my magpie instinct was more drawn to the colour element than the gradations in size. I linked each numerical height with its colour so strongly that yellow was 5 and orange was 10. The conflation held its own secret fascination.

I deduced that what the shorter rods lacked in height they made up for in brightness of hue as if each rod were granted an equality in power, balancing height with intensity of colour. But why was red two and pink four and not the other way round? Could there be a hidden significance to the order?

I might like to think all of this was some kind of synaesthesia but it was more likely an early manifestation of OCD or an autistic tendency. Colours and car registration letters, numbers on front doors, the colours of clothes worn by particular people on particular days of the week quickly followed.

days of the week quickly followed.

Unfortunately my appreciation of the rods failed to translate into lasting mathematical ability. I obtained an ‘unclassified’ in my O level, the lowest possible grade (not proud of it in a “I’m hopeless at maths!” kind of way, just saying).

Tables or rods?

Child centred learning was central at my primary school.

Certainly in our earlier years, the emphasis was more on discovery not instruction, peer group learning rather than whole class teaching.

I even remember one teacher, straight out of training college, asking her class – did we want to do sums or painting? Painting always won out so maths was neglected until at the age of ten I had a crash course in learning my times tables. The class chanted them and my mother made me say them out loud or would suddenly demand over morning’s Golden Nuggets “What are twelve fours?”

But perhaps it was too little too late.

Seeing and doing

Still available but far less popular today, Cuisenaire rods now come in plastic which seems unimaginable as the woody feel and smell of them was very much a part of their appeal. Rod No 4, the pink one, is now, for some reason, purple.

The most enjoyable thing to do with the set was – and still is – to build a pyramid.

Starting with the orange 10s, use four rods of each colour to form an overlapping square, working your way up through the blues, browns and blacks until you end up with a tight square of four white 1s on top.

Like this:

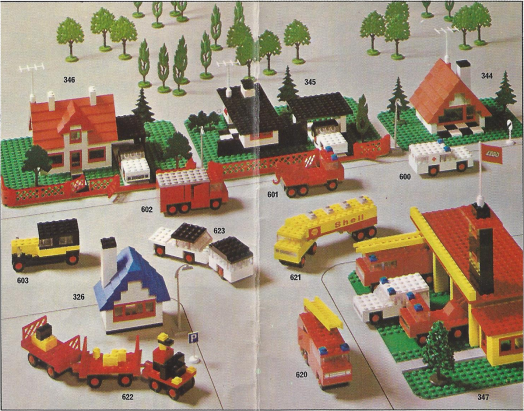

I was never the most dextrous of children and not at all mechanically minded but Lego I liked.

I was never the most dextrous of children and not at all mechanically minded but Lego I liked.

actually Danish, sensibility. Even that vertical striped logo suggests an idealistic amalgam of Euro flags.

actually Danish, sensibility. Even that vertical striped logo suggests an idealistic amalgam of Euro flags.

The publicity is fascinating. Boldly colourful pictures of clean-cut børn and Startrite graphics strongly evoke the times

The publicity is fascinating. Boldly colourful pictures of clean-cut børn and Startrite graphics strongly evoke the times