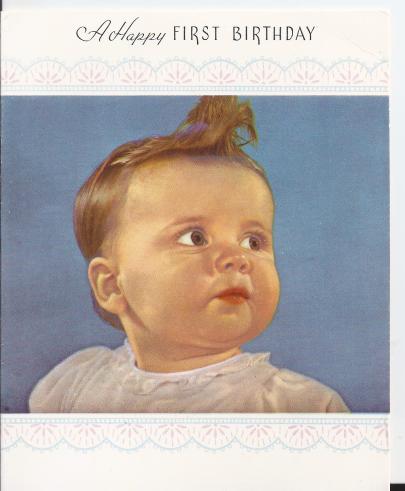

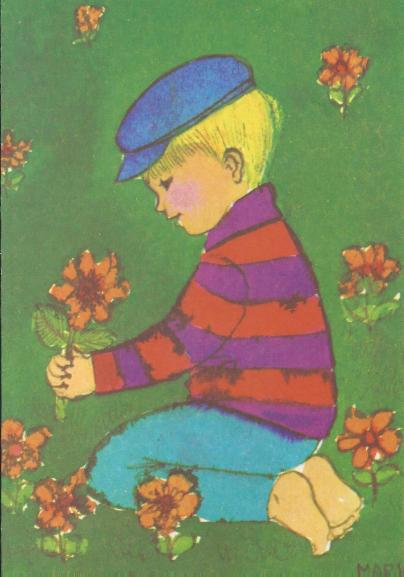

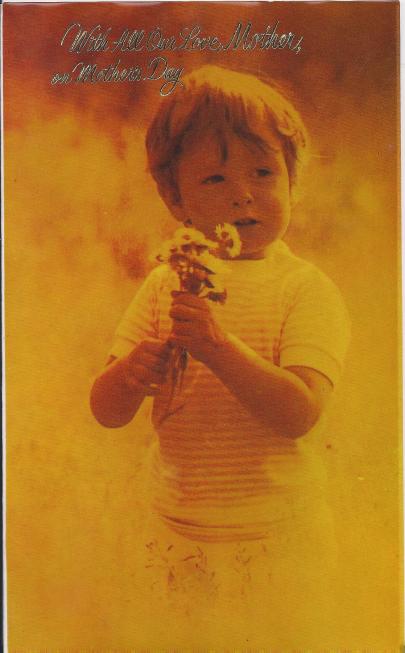

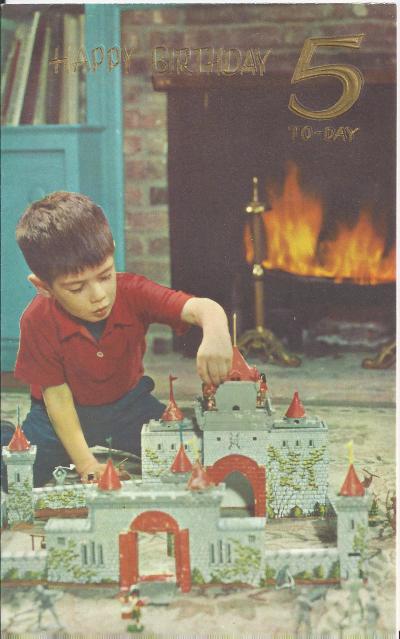

10 Downing Street, London, October 1969.

It seems extraordinary that such photo opportunities were presumably commonplace back then. Mine had nothing to do with an invitation or acceptance of any kind of accolade, it was merely incidental. Perhaps a child was ushered away before me and another ushered on afterwards. How many of us have a similar photo in our family album?

I remember nothing of that half-term day trip to London. The significance of the location would have been entirely lost on me as a five year old. The background could almost be a ‘Mary Poppins’ set, there’s a kind of quaintness to the whole scene: my Uncle Earnest’s conversation with a very at ease bobby; my post box red jumper, school socks and oh so shiny shoes.

The date is prescient. ‘The Troubles’ began a month later, no doubt precipitating a significant increase in security.

Ten years on

Fast forward almost a decade and I stood as part of a small crowd, fenced off opposite the entrance to Number 10 where reporters stand today. This was as close as we were allowed to get. After what felt like a long wait but was probably only fifteen minutes, the then PM, James Callaghan, emerged to a round of applause and muted cheers. Such polite deference (we were members of the public not Labour Party supporters) seems surprising from a 2020 perspective. A brief wave and then Uncle Jim got into a waiting limousine and was driven swiftly away, probably to PMQs. I would say this was autumn 1978. The winter of Discontent lay just round the corner.

Me in time

When I rediscovered this transparency last autumn, I instantly felt a flush of pride, a kind of innocent, poignant pride. I’m not at all given to feeling proud through association with public monuments or official occasions so the emotion caught me by surprise.

Perhaps it was the contrast between one little boy on the steps of the most prestigious address in the United Kingdom where that little boy just happened to be me. And perhaps it was an instant realisation that such an incongruously domestic photo would be an impossibility today.